What benefits territorial reform can actually provide

Author: Paweł Swianiewicz

Paweł Swianiewicz, a professor of economics, heads the Department of Local Development and Policy at the Faculty of Geography and Regional Studies, and the Doctoral School of Social Sciences at the University of Warsaw. Between 2005 and 2010, he was president of the European Urban Research Association (EURA). Currently he is a member of the Steering Committee of the Standing Group on Local Government and Politics of the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR). Swianiewicz’s teaching and research focus on local politics, local government finance, and territorial administrative reforms in Europe. His empirical research concentrates on Poland, as well as on comparative studies of decentralization and local autonomy in Central and Eastern Europe.

Executive summary

Territorial reforms are among the most politically difficult, since they typically meet with resistance. And yet, they have been common across Europe. At least 20 European countries have undertaken municipal territorial reform during last two decades alone.

Researchers do not all agree in their conclusions on the actual outcomes of the reforms, nor do they share the optimism of many politicians advocating for the amalgamation of municipalities. While most studies are unanimous that municipal territorial reforms bring savings in administrative costs, other economic gains from such reforms are less obvious and depend very much on specific local conditions and the details of the implemented changes. Moreover, there is little doubt that municipal mergers can reduce people’s interest in local public affairs, and the level of trust and satisfaction with the way local governments work. In short, they can have negative effect on local democracy.

To complete territorial reform requires coordination with other dimensions of the reconfiguration of local government, such as functional decentralization and inter-governmental finance. In European practice, different models have been applied of “coupling” territorial with other reforms. Sometimes functional decentralization comes first and requires territorial adjustments; in other cases, territorial reform stimulates functional or financial decentralization.

Most amalgamation reforms have been implemented in a top-down manner by central governments, although some were either voluntary—even if spurred by incentives—or at least had a voluntary phase. Ukrainian reform belongs to the most successful, at least in Central and Eastern Europe, in terms of achieving a large proportion of amalgamations through voluntary agreements among local governments.

Territorial reforms in Europe

This article summarizes the experience of recent territorial reforms in Europe through an extensive review of existing reports and academic studies. The focus is not on any particular case, but on a comparative perspective gathering lessons learned from reforms implemented in various countries. This article limits the discussion even further to boundary changes at the municipal level, leaving aside those concerning provinces, counties or districts. Evidence and conclusions are presented so as to allow their application to Ukraine’s reform.

Territorial amalgamation reforms are among the most politically difficult. As Paddison (2004, p. 25) notes: It is almost a law of local boundary restructuring, that there will be powerful forces intent on maintaining the status quo. Part of the reason is institutional inertia. Baldersheim & Rose (2010) conclude: Once institutions are established, they set limits to the future choices that are available. This resistance may be explained on a rational choice level. Consolidation reform means a reduction in the political posts available, such as mayors and councillors. For others, it can mean the loss of prestige or even job security. As Paddison (2004, p. 34) states bluntly: Local (municipal) elites are unlikely to vote for territorial suicide, thus resistance to change is a very common pattern. Moving to concrete examples of emotions and opposition often raised by territorial reforms, one of the most extreme cases was a hunger strike in the town of Dorothea, during Swedish municipal boundary reform in 1970s (Brink 2004). In one of the Länder in eastern Germany, the amalgamation of counties brought out the largest street demonstrations since the fall of the Berlin Wall. There have been other examples of conflicts involving mass participation by local residents over amalgamation reforms across Europe in recent decades.

Given this kind of opposition, it is surprising how often such reforms have been implemented in Europe since World War II. The first wave of European territorial consolidation reforms took place between the 1950s and 1970s, in several countries in Western Europe, mainly the more northern ones: Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Germany. There were two major factors beyond those reforms. First, rooted in the economy of scale paradigm, stressed that local services could be delivered more cheaply and in better quality by larger local administrations. But perhaps even more important was the “adjustment logic” of the reforms. After the end of WWII, Europe saw the “rise of the welfare state,” in which public provision of a number of services, especially those related to social welfare, like education, healthcare and social protection, grew in importance and coverage. In several countries, local governments were expected to play a central role in this model, so territorial restructuring became necessary since very small local governments were unable to take responsibility for the new functions related to the new welfare state.

Meanwhile, developments in Central and Eastern Europe were very different. In the beginning of 1970s, the process of territorial consolidation took place throughout Eastern and Central Europe. That change was largely inspired by a very strong, widespread belief in economies of scale among communist governments. Polish communities were amalgamated in 1973 and their number reduced from more than 4,000 to about 2,400. In Hungary, the number of municipalities went from 3,021 in 1962 to 1,364 by 1988. In Czechoslovakia, the number of municipalities was similarly reduced from 11,459 in 1950 to 4,104 by 1988. In Bulgaria, the number of municipalities went from 2,178 in 1949 to 255 at the end of 1980s. Similar reforms took place in Romania and Yugoslavia. Of course, East European territorial reforms were introduced in an authoritarian, undemocratic way, without any broad public debate or consultations.

The beginning of 1990s was marked by territorial fragmentation in many of these countries, a process that might be seen as a reaction to all the forced amalgamations of 1970s.[1] When the number of municipal governments at the beginning and the end of the decade are compared, it’s clear that the numbers more than quadrupled in Croatia and Macedonia, more than tripled in Slovenia, more than doubled in Hungary, went up more than 50% in the Czech Republic and 30% in Bosnia and Herzegovina. More modest territorial fragmentation could be seen also in Slovakia, Romania, Ukraine, and some other countries. What is important is that all of these cases were the driven by bottom-up pressure from local communities. Territorial fragmentation was never a process planned by central governments, although perhaps the one exception to this rule was Romania, where the break-up of municipalities was encouraged by the central government at the end of 20th and beginning of 21st century. Indeed, the central governments did not interfere much in this process, considering that to block municipal secessions would be a violation of democratic principles and local autonomy.

This period of territorial fragmentation was obviously endogenous in nature, being as it was related to the post-communist transition, but at the same time it had support in the more general trend in Europe. Erlingsson et. al. (2015: 210) note that at the beginning of 1990s, it was a common view that the era of large administrative structural reforms was over (see also Marcou 1993), and the trend was rather the reverse. In Sweden, a centre-right government won the election in 1991 and subsequently took a favourable stance towards municipal secessions, that is, the wish to move back to smaller—and greater numbers of—geographical units.

But the dominant trend soon changed again in favour of territorial amalgamation. During the first two decades of this century, territorial reforms leading to substantial reductions in the number of municipalities have been introduced in some 20 European countries, including:

- Northern Macedonia (2002)

- Georgia (2006)

- Denmark (2007)

- Latvia (2009)

- Greece (2011)

- Albania (2015)

- Ireland (2015)

- Estonia (2017)

- Northern Ireland (2017)

To that list can be add reforms in parts of federal countries, where municipal boundaries are often decided on a regional, not federal level. In this same 20-year period, municipal amalgamation reforms were implemented in:

- 5 German Länder

- 1 Austrian Land

- 5 Swiss cantons

In some countries, reforms did not take place in any one particular year, but the number of local governments has been reduced step-by-step, sometimes by a few mergers every year, and the number of municipalities nowadays is substantially lower that 20 years ago:

- England

- Finland

- the Netherlands

- Iceland

Last but not least, some countries have undertaken municipal boundary reforms very recently and the process has not been finished yet:

- Armenia

- Norway

- Cyprus

- Ukraine[2]

This new wave of territorial reforms has often been motivated by demand for cost saving and financial austerity measures, especially true of reforms implemented after the 2008 financial crisis. But other arguments by the proponents of the reforms have focused on the capacity of local administrations to deliver good quality services to their communities.

As a result of the processes described here, the number of municipalities in Europe has been fluctuating. Available data from 40 European countries shows that the total number of municipalities in 1990 was around 116,000. With the reverse trend towards territorial fragmentation in Central and Eastern Europe, the numbers grew to 120,000 in 2000, but then started to go down again, to around 106,000 in 2014 and 102,000 in 2018. The magnitude of changes in territorial organization of individual European countries is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Municipal territorial reforms in Europe since 2000

|

|

average population size of municipality

|

proportion of municipalities:

|

||||

|

before

(year - size)

|

after

(year - size)

|

below 1,000

|

below 10,000

|

|||

|

before

|

after

|

before

|

after

|

|||

|

Albania

|

2011- 10,840

|

2016 - 73,000

|

5%

|

0%

|

73%

|

5%

|

|

Armenia (unfinished)

|

2015 - 3,445

|

2019 - 6,243

|

49%

|

26%

|

97%

|

92%

|

|

Austria - Styria

|

2013- 2,254

|

2015 - 4,256

|

38%

|

6%

|

98%

|

95%

|

|

Denmark

|

2006 - 20,027

|

2007 - 55,582

|

0%

|

0%

|

48%

|

4%

|

|

Estonia

|

2016 - 6,343

|

2017 - 17,118

|

19%

|

4%

|

92%

|

59%

|

|

Finland

|

2000 - 11,441

|

2018 - 17,721

|

5%

|

5%

|

76%

|

68%

|

|

Georgia

|

2006 - 4,358

|

2007 - 67,489

|

24%

|

0%

|

96%

|

6%

|

|

Greece

|

2010 - 10,573

|

2011 - 33,241

|

11%

|

4%

|

79%

|

25%

|

|

Iceland

|

2000 - 2,281

|

2014 - 4,401

|

75%

|

57%

|

96%

|

92%

|

|

Ireland

|

2013 - 167,466

|

2014 - 183,166

|

0%

|

0%

|

0%

|

0%

|

|

Latvia

|

2008 - 4,326

|

2010 - 17,819

|

39%

|

0%

|

95%

|

69%

|

|

Luxembourg

|

2001- 3,747

|

2018 - 5,902

|

25%

|

1%

|

94%

|

90%

|

|

Northern Macedonia

|

1994 - 16,444

|

2004 - 24,389

|

4%

|

0%

|

58%

|

38%

|

|

Netherlands

|

2000 - 29,542

|

2018 - 45,213

|

0%

|

0%

|

23%

|

6%

|

|

Norway

|

2015 - 12,070

|

2020 - 15.078

|

6%

|

6%

|

73%

|

68%

|

|

Switzerland - Fribourg

|

2000 - 994

|

2017 - 2,315

|

76%

|

38%

|

99%

|

98%

|

|

UK - England

|

2001 - 139,572

|

2011 - 163,589

|

0%

|

0%

|

0%

|

0%

|

|

UK - Northern Ireland

|

2014 - 70,788

|

2018 - 171,058

|

0%

|

0%

|

0%

|

0%

|

The impact of territorial reforms

What gains and benefits were expected from these reforms or promised by those who initiated them? The first promise was related to economies of scale, which suggested that economy of scale exists not only in industrial production but also in services delivered by local governments. In fact, the most direct empirical evidence is related to administrative services. So, the assumption was that the provision of services by larger local governments might be cheaper. The concept of economy of scale is based on the distinction between constant and variable costs of services. A high share of constant costs allows for minimized marginal costs with an increase in the scale of production. The scale effect is more visible in services in which constant costs play a more important role, and so, changes in the scope of local government services may change the optimal point in a U-shaped curve (Bikker and Van der Linde 2016; Hirsch 1968).

The second aspect potentially important in times of economic turbulence is related to economic resilience and the ability to manage finances and economic development. Here, there was also a belief that larger local governments might be more efficient in this respect (Keating 1995, Walsh 1996), so the demand for territorial reforms could increase in times of economic crisis.

Another important promise of the reformers was that large local governments would have greater capacity to deliver a wider scope and better quality of services. One of the reasons would be attracting more highly qualified administrative staff that might be more specialized than in very small town-hall administrations (Keating 1995, Sharpe 1995).

Democratic arguments are less often raised by reformers. But in some cases it is suggested that amalgamation reform may have a positive impact through the increased competitiveness among local elites and increased public interest due to the larger scope of local government functions.[3] However, this contrasted in Robert Dahl’s classic 1967 work:

“The smaller the unit, the greater the opportunity for citizens to participate in the decisions of their government – yet the less of the environment they can control. Thus, for most citizens, participation in very large units becomes minimal and in very small units it becomes trivial.”

Consequently, scholars commonly believe that in decisions on the size of local governments, there is a trade-off between economic and democratic performance.

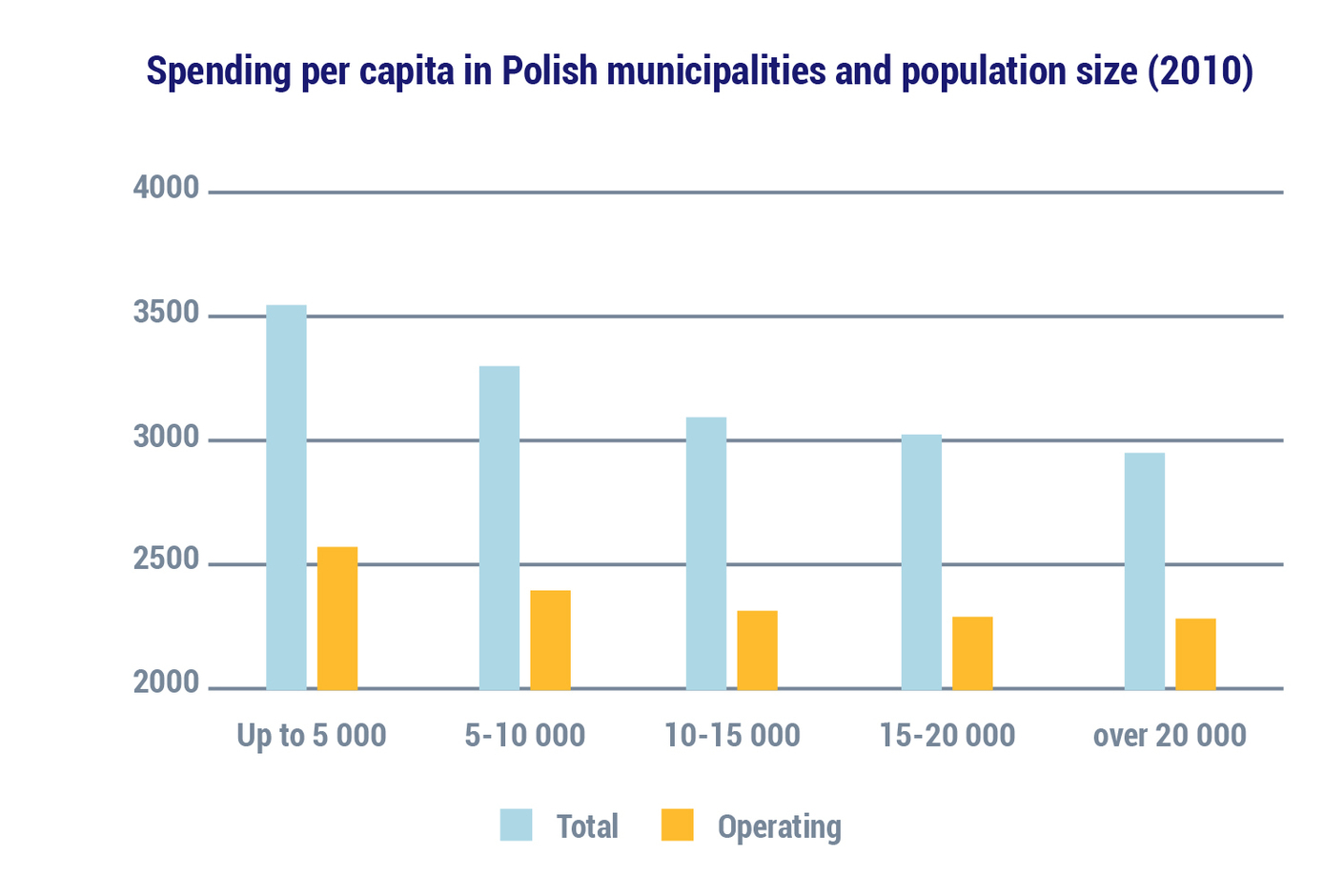

Projections by proponents of reforms are often based on insufficient data or on simplistic interpretations of evidence. In particular, many politicians use simple comparisons of the performance of smaller and larger local governments as an argument supporting reform. The assumption is that the worse performance of smaller local units may be overcome by territorial reform. There are several examples of this kind of logic, including in the 2013 report of the Polish Ministry for Public Administration, whose arguments are illustrated in Figure 1. Both total and operating expenditures per capita are higher in small communities. Therefore, proponents of the reform argued, amalgamating the smallest municipalities would bring significant savings in public spending.

Figure 1. Per capita spending in Polish municipalities and population size, 2010

Source: Ocena sytuacji samorządów lokalnych (2013), Warszawa: Ministerstwo Administracji i Cyfryzacji. [Evaluation of the local government situation] http://eregion.wzp.pl/sites/default/files/ocena-sytuacji-samorzadow-lokalnych.pdf

The problem with this argument is that the correlation visible in Figure 1 is not necessarily the consequence of a causal relationship between size and per-capita spending. There might be several other reasons that should be verified before coming up with a final conclusion. First, the figure does not tell us anything about the quality of services. Second, alternative organizational arrangements of various services lead to different accountancy practices: for instance, if a service is outsourced to a municipal company, spending on that service is not visible in the municipal budget report. Thirdly, the difference in expenditures might be not due to size difference but, among others, due to the fact that smaller local governments often administer sparsely populated areas, which contributes to higher unit costs of services and skews statistics. Thus, the merger of two sparsely populated municipalities would not contribute to cost savings.

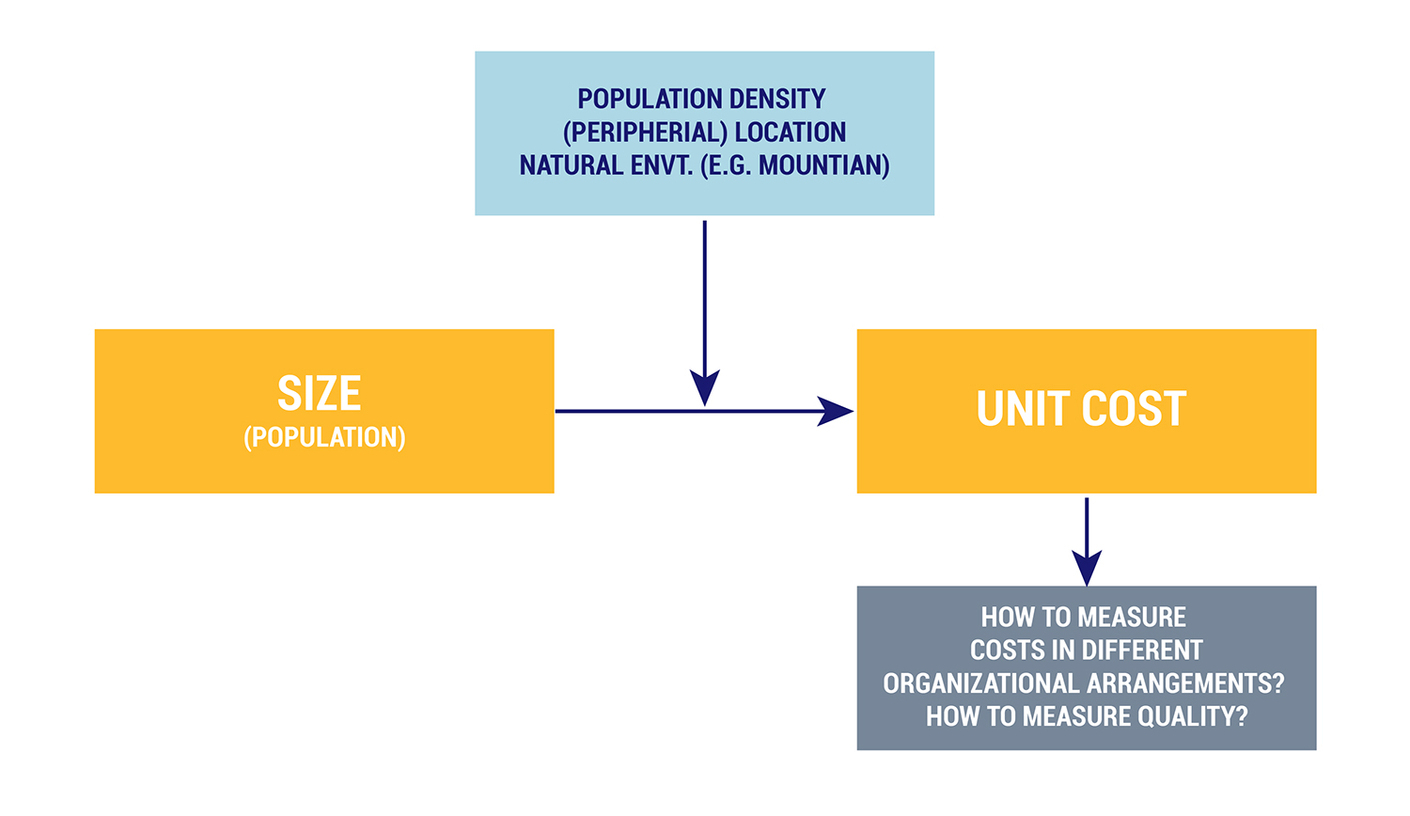

Scepticism towards a simplistic belief in economies of scale is evident in several World Bank reports, concluding that population size is not a decisive variable in determining the cost or quality of public services: where populations are geographically dispersed, there are few economies of scale to be gained by incorporating them into a single larger jurisdiction (Fox, Gurley 2005). There might be also several other reasons beyond the seeming relationship that are very difficult to observe and that make suspect any conclusions based on such simple comparisons in relation to the impact of territorial reforms. The complexity of these relationships is illustrated in Figure 2.

These complications do not mean that academic studies have nothing to say about the results brought by past territorial reforms. Most academics agree that the most reliable results in terms of identifying causal relationships can be brought about by quasi-experimental statistical methods. Over the past 10 years, there have been close to 50 such studies published, identifying the various effects of territorial reforms in different countries.

Figure. 2. Relationship between size of local government and unit costs of provided services

The conclusions from those studies confirm that territorial amalgamation reforms contribute to a definite reduction in administrative costs.[4] But when it comes to the costs of other services, capacity for financial management and quality of delivered services, the results are much less clear: different studies have led to different conclusions, depending on specific local conditions. Still, several studies are almost univocal in discovering the negative impact of amalgamation on local democracy: after amalgamation, local residents became less interested in local issues and their trust and satisfaction with their local administration’s performance went down.

At the same time, larger local government units saw the level of electoral competition go up. It has been also observed that local governments tended to make costly financial decisions, related to borrowing and investments, directly before amalgamation, especially if it was top-down imposed by the central government. As A. Tavares (2018) concluded:

“The survey of the literature recommends caution regarding the expectations of amalgamation reforms, and not the unbridled optimism we often see in consultancy and governmental reports.”

Still, the conclusions of such studies cannot be simply extrapolated to other countries. Most of the quasi-experimental studies in Europe were tested on data from Scandinavia—Denmark, Finland and Sweden—, followed by fewer studies from Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Austria, and only sporadic ones from Central and Eastern Europe—two studies on Poland. Existing analyses rarely include cases of amalgamation of very tiny local governments, that is, of communities with fewer than 500, which were not that rare in the case of Ukraine. So, we cannot be sure that the conclusions drawn from mergers of larger municipalities would be confirmed in Ukraine as well. Most likely mergers of very tiny towns and villages would bring more visible economic gains. In any case, the recent decentralisation reforms in Ukraine provide a unique laboratory for potentially very useful academic studies in this respect.

Voluntary or compulsory amalgamations?

Territorial reforms can be classified in several ways, depending on the various approaches to implementation: the time span between decision and implementation, the depth of territorial changes, and so on. But the distinction that might be especially interesting from the point of view of Ukraine is between bottom-up, voluntary—even if often inspired and incentivised by the central government—mergers and top-down, compulsory ones in which a decision by the central government or legislature is imposed on local communities, sometimes against their will. Some elements of listening to opinions of local communities have to be present in every reform, since the European Charter of Local Self-Government stipulates that public consultations over boundary changes are mandatory. But the results of such consultations need not be binding, so, in practice, there is leeway for top-down, forced reforms.

The distinction between compulsory and voluntary reforms is quite useful, but the borderline between the two types is not fixed. Political pressure and strong incentives, both financial and functional, as well as ways of sanctioning municipalities that are not spontaneously enthusiastic about the reform—financially, through the modified inter-government transfer system—are sometimes so strong, that this approach is not much different from coercion. The institutional framework is an important factor. In several European countries, legal regulations do not allow for municipalities to be forced to merge. Belgium, Iceland, Spain, most Swiss cantons, Bulgaria, and the Czech Republic are examples. But in several other cases, such as Denmark, Sweden, Ireland, Greece, Latvia, Estonia, Albania, and Georgia, reforms have at least partly been imposed by the centre.

In several countries, territorial reforms had two consecutive stages: voluntary and compulsory. In the first phase, local governments were allowed to freely negotiate mergers with neighbours, and the only limitation was that the new local government unit had to meet certain criteria defined in central or regional—in case of federal countries— policy. In the second phase, those local governments who had not submitted acceptable proposals on their own, were in a position to be forced to merge according to a top-down plan. This was the case with Danish, Norwegian and Estonian reforms. And this is the case with the current Ukrainian reforms, as well. In several cases across the continent, attempts to stimulate voluntary reforms through incentives failed. In Poland, for instance, strong financial incentives introduced over a decade ago have resulted in only one municipal merger. Attempts to incentivise voluntary amalgamations also failed in Greece and Latvia.

In some very strict circumstances, highly institutionalized inter-municipal cooperation could be seen as an “escape” from amalgamation. Finland is a good example of such a process, but perhaps the best-known case of overriding difficulties related to territorial fragmentation by well-developed inter-municipal cooperation is France (see e.g. Hertzog 2018).

It is not easy to define what are the conditions for successful voluntary amalgamations, but definitely a proper combination of financial and functional incentives can help. Ukraine’s decentralisation reform introduced since 2015 may be considered one of the most successful attempts to stimulate voluntary amalgamations. Strong incentives that definitely contributed to this success included:

- additional financial transfers available immediately after the reform;

- the right to take over responsibility for important additional functions or competences provided until then by a higher tier of administration—the county level;

- greater financial autonomy for local communities, as amalgamated local governments were included in the general system of inter-government transfers allocated by a formula.

But voluntary amalgamations, if not sufficiently coordinated, present a danger that has been clearly observable in Ukraine. They can lead to chaotic results and asymmetrical territorial organization, in which new, enlarged territorial units exist next to small local governments that refused to join the merger process. This can make the provision of some public services for the entire area extremely complicated and inefficient. That is why the second stage, compulsory amalgamation, is so important to the overall success of the reform.

Threshold criteria for amalgamated municipalities

Territorial reform plans often include the minimum criteria that have to be met by the reorganized local government administrations. Similar criteria have typically been introduced in countries where there were no plans for territorial reforms but there was pressure to fragment municipalities, that is, secessions or de-amalgamations. In such cases, the threshold defined the criteria that had to be met by the units applying to break away from a larger local unit.

The most typical criteria are related to minimal population size, although they can be defined at very different levels. In some countries the threshold is very low, such as 1,000 residents in the Czech Republic, 1,500 in Romania, 3,000 in Slovakia, and 4,000 in Latvia. The mid-range thresholds have been defined, such as 5,000 in Slovenia and Estonia, 6,000 in Bulgaria, and 10,000 in Greece. Estonia provides a good example of a country in which the general threshold is accompanied by several exceptions in case of a special local situation. The general threshold is 5,000 residents, but a lower number, starting at 3,500, is allowed for: municipalities located on islands, communities of “cultural significance,” and larger territories with especially low population density. In still other countries, the population threshold is defined at a much higher level, such as 15,000 in Lithuania and 20,000 in Denmark.

But population size is not the only type of criteria openly formulated. A review of European reforms shows that criteria related to existing technical and social infrastructure, the expected financial viability of new local governments—this criterion is very differently applied—, positive demographic dynamics, and even maximum distance to the city hall. Some reforms, such as Swedish, Albanian and Latvian, made a clear reference to central place theory and the expectation that new municipalities should have a natural urban centre. Latvia even added an additional definition of the minimum population size of such a centre.

Coupling with other reforms

Territorial reform is rarely an end in itself, so boundary changes generally go hand-in-hand with other changes in relations among different levels of government. There are two types of arguments that come up in this situation. First: enlarging local government units means they should have greater capacity to provide various services, and the scope of their functions will also widen—decentralization leading to more functions. If, after amalgamation, larger units have greater capacity, they can be offered a higher level of autonomous decision-making. This autonomy can concern providing various individual services, but it can be also related to financial management, that is, increased financial autonomy regarding tax policies, borrowing regulations, decisions on spending structures, and so on.

The second argument is based on the reverse causality: decentralisation of a wider scope of functions or financial decentralisation can lead to demand for larger organizational and/or management capacity in local governments. This, in turn, can lead to an “adjustment type” of territorial amalgamation, in which territorial reform follows or tries to catch up to earlier decisions concerning the allocation of functions. This logic of “adjustment reform” has often been used to interpret the earlier wave of amalgamations of the post-WWII era, such as in Scandinavia and in the United Kingdom.[5] The more interesting question is whether this same logic can be applied to interpretations of territorial reforms implemented in 21st century Europe.

More detailed empirical evidence makes it possible to conclude that, in most cases, boundary changes have been interconnected with broader changes in local government systems.

Figure 3: Relationship between municipal territorial reforms and broader changes in local autonomy or policy scope

|

|

Changes in local autonomy and/or policy scope parallel with or shortly after territorial reforms

|

||

|

no

|

yes

|

||

|

Increase in local autonomy and/or policy scope in the decade before territorial reforms

|

no

|

Unfinished reforms

Austria (Styria), Georgia, Ireland, Latvia

|

Incentivized decentralisation reforms

Albania, Armenia, Denmark, England, Estonia, Greece, Ukraine

|

|

yes

|

Adjustment reforms

Finland, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway

|

Continuous decentralisation reforms

Macedonia

|

|

These interconnections may be either in the form of adjustments, where earlier changes in the direction of greater municipal autonomy call for subsequent territorial amalgamation, or incentivized decentralisation, where the expanded functions of municipal governments go together or shortly after territorial consolidation. Where changes have taken place before the territorial reform, but continued in subsequent periods, this might be called “continuous decentralisation reform,” in which territorial amalgamation is just one, albeit very important, component. There have also been some exceptions to that rule, such as territorial reforms that are difficult to explain through the logic of functional decentralization.

Conclusion

Ukraine’s territorial reform definitely belongs to the group of incentivised decentralisation reforms. Newly amalgamated municipalities are expected to take over a much broader scope of functional responsibilities, mainly inherited from counties, and are also given a much stabler, broader base of financial resources.

A few more steps are necessary to consider Ukraine’s reforms to be successfully completed. First is to finalize the administrative or compulsory amalgamations in a way that will not raise too many conflicts with and within local communities and that will result in a comprehensive map of territorial reorganization. Second is to clarify the future relationship between the counties and amalgamated municipalities, given that the lowest level of government is effectively taking over most of the functions previously provided by the counties. Third is the highly recommendable step of introducing a fully-fledged monitoring system to track the impact of the reforms, which would help to plan any further adjustments, gauge the positive effects and mitigate negative ones.

On a positive note, looking at the Ukrainian experience through the lens of a wider European perspective, it’s clear that a successful completion of the reform in Ukraine is possible.

References and further readings

Askim J., Klausen J.E., Vabo S.I., Bjustrøm K. (2017), “Territorial upscaling of local governments: a variable-oriented approach to explaining variance among Western European countries,” Local Government Studies, #43(4), pp 555-576.

Baldersheim, H., Rose. L. (2010) Territorial Choice: The Politics of Boundaries and Borders, London: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Bikker, J., and Van der Linde, D.. (2016), “Scale economies in local public administration,” Local Government Studies #42(3), pp 441–63.

Brink, A. (2004). “The break-up of municipalities: Voting behavior in local referenda,” Economics of Governance, #5(2), pp 119-135.

Dahl, R. A. (1967), “The city in the future of democracy,” American Political Science Review, #61(4), pp 953-970.

Erlingsson, G., Ödalen, J., Wångmar, E. (2015), “Understanding large-scale institutional change: social conflicts and the politics of Swedish municipal amalgamations 1952-1974,” Scandinavian Journal of History, 2015, Vol. 40, #2, pp 195–214 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03468755.2015.1016551

Fox, W.F., Gurley, T. (2005), “Will consolidation improve sub-national government?” Policy Research Working Paper 3913, Washington: World Bank Report.

Gendźwiłł, A., Kurniewicz, A. Swianiewicz, P. (2020), “The impact of municipal territorial reforms on economic performance of local governments. A systematic review of quasi-experimental studies,” Space and Polity, DOI: 10.1080/13562576.2020.1747420;

Hertzog, R. (2018), “Inter-municipal cooperation in France: A continuous reform, new trends,” in F. Teles, P. Swianiewicz (eds.) Inter-municipal cooperation in Europe: Institutions and governance, Palgrave-Macmillan, p. 133-156.

Hirsch, W.Z. (1968), “The supply of urban public services,” in H.S. Perloff and L. Wingo (eds.), Issues in Urban Economics, pp 477–525. Baltimore: John Hopkins Univ. Press.

Keating, M. (1995), “Size, Efficiency and Democracy: Consolidation, Fragmentation and Public Choice,” in D. Judge, G. Stoker, H. Wolman (eds.), Theories of Urban Politics, Sage, London–Thousand Oaks–New Delhi.

Kjær, U. (2007), “The decreasing number of candidates at Danish local elections: Local democracy in crisis?” Local Government Studies, #33(2), pp 195-213.

Kjellberg, F. (1985), “Local government teorganization and the development of the welfare state,” Journal of Public Policy #5(2), pp 215–239. doi:10.1017/S0143814X00003032.

Marcou, G. (1993), “New tendencies of local government development in Europe,” in R Bennett (ed.) Local Government in the New Europe, London: Belhaven Press, pp 51-66.

Newton, K. (1982), “Is small really so beautiful? Is big really so ugly? Size, effectiveness, and democracy in local government,” Political Studies, #30(2), pp 190-206.

Paddison, R. (2004), “Redrawing local boundaries: Deriving the principles for politically just procedures,” in J. Meligrana (ed.), Redrawing Local Boundaries: An International Study of Politics, Procedures, and Decisions, Vancouver – Toronto: UBC Press.

Ryšavý, D., Bernard, J. (2013), “Size and local democracy: The case of Czech municipal representatives,” Local Government Studies #39(6), pp 833-852.

Sharpe, L. J. (1979), Decentralist Trends in Western Democracies, London: Sage.

Sharpe, L.J. (1995), “Local government: Size, efficiency and citizen participation,” in L.J. Sharpe (ed.), The Size of Municipalities, Efficiency and Citizen Participation, Local and Regional Authorities in Europe, #56, pp 9–59. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Swianiewicz, P., Gendźwiłł. A., Zardi. A. (2017), Does Size Matter? Toolkit of Territorial Amalgamation Reforms in Europe, Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Tavares, A.F. (2018), “Municipal amalgamations and their effects: A literature review,” Miscellanea Geographica #22(1), pp 5–15, DOI: 10.2478/mgrsd-2018-0005.

Verba, S., Nie, N.H. (1972), Participation in America, New York: Harper and Row.

Walsh, K. (1996), “Public services, efficiency and local democracy,” Rethinking local democracy, pp. 67-88, Springer.

Copy editor: Lidia Alexandra Wolanskyj

All terms in this article are meant to be used neutrally for men and women

Prof. Paweł Swianiewicz has participated at the International Expert Exchange, "Empowering Municipalities. Building resilient and sustainable local self-government", organized by U-LEAD with Europe Programme in December 2019. His speech delivered during one of the workshops is to a great extent depicted in this article. Despite its late publication, the article is still of significant relevance for the current discussion on decentralization reforms’ next steps in Ukraine.

In the name of the U-LEAD with Europe Programme, we would like to express our great appreciation and thanks for both inputs of Prof. Swianiewicz. The article will be included in future online publication Compendium of Articles.

Compendium of Articles is a collection of papers prepared by policymakers, Ukrainian and international experts, and academia after International Expert Exchange 2019 and 2020, organized by U-LEAD with Europe Programme. The articles raise questions in the fields of decentralization reform and regional and local development, relevant for both the Ukrainian and the international audience. The Compendium will be published online in Ukrainian and English languages on the U-LEAD online recourses. Please, follow us on Facebook to stay informed about the project.

[1] Since most break-ups of municipalities were reversing amalgamation decisions made previously, the process is sometimes referred to as “de-amalgamation.”

[2] Please note that the article was written in early 2020 when the process of amalgamation in Ukraine had not been completed yet.

[3] See e.g. Verba and Nie 1972, Kjær 2007, Ryšavy and Bernard 2013, Newton 1982.

[4] Comprehensive reviews of studies referred to in this section may be found, e.g., in: Swianiewicz et al. 2017, Tavares 2018, Gendźwiłł et al 2020. See reading list at end.

[5] Sharpe 1979, Kjellberg 1985, Askim et al 2017.

11 December 2024

Синергетичний підхід: як працює підтримка ветеранів у Калуській громаді

Синергетичний підхід: як працює підтримка...

Як працює механізм підтримки ветеранів війни та членів їхніх сімей на рівні громади, що можна вважати успішними...

11 December 2024

Chornomorsk reboot veteran policy

Chornomorsk reboot veteran policy

After returning from the battlefield to the home, veterans face various challenges: rehabilitation, employment, and...

11 December 2024

17 грудня - тренінг «Відновлення втраченої...

17 грудня 2024 року (вівторок), о 10:30 розпочнеться тренінг на тему: «Відновлення втраченої інформації та документів...

10 December 2024

Ветеранський кемпінг та безпека пішоходів: учасники конкурсу Громада на всі 100

Ветеранський кемпінг та безпека пішоходів:...

10 листопада завершилося голосування та вибір 40 фіналістів серед територіальних громад, які подалися на конкурс...